I freely admit that what you're about to read borders on political fiction. There's absolutely no realistic chance of a non-Malay taking over the reins as Malaysia's leader right now. However, it may also be why the country is still likely to suffer considerable political chaos for many years to come.

And that's why I've decided to write about it - highlighting the possibility, how relevant it is in current reality and that it could, in fact, be great for the country - including its Malay majority.

More politics than governance

Witnessing all that's been going on since Pakatan Harapan took over in May last year, you just can't help but think that it is not the change that was expected by the voters.

Some broken pledges or the misleading switch from GST to SST can be forgiven - all political parties tend to overpromise to win public support and later have to deal with the reality of governance, where cash is often in short supply. It's fine as long as the country is on the right track over the long term.

Worrisome is, however, the amount of time spent politicking instead of actually managing affairs in the best interest of Malaysia and its people.

I have written about a chain of completely senseless provocations against neighbouring Singapore already (here, here & here) - but it is clear that problems are created not only in foreign relations but domestically as well.

The latest reports of infighting in PKR are just a few in a string of news about wrestling over power and influence in Malaysia.

It is deeply disconcerting to see that in the wake of a truly historical victory over corrupt Barisan Nasional, so many people in the winning camp prefer to engage in political quarrels to inflate their personal standing rather than contribute to fixing the country.

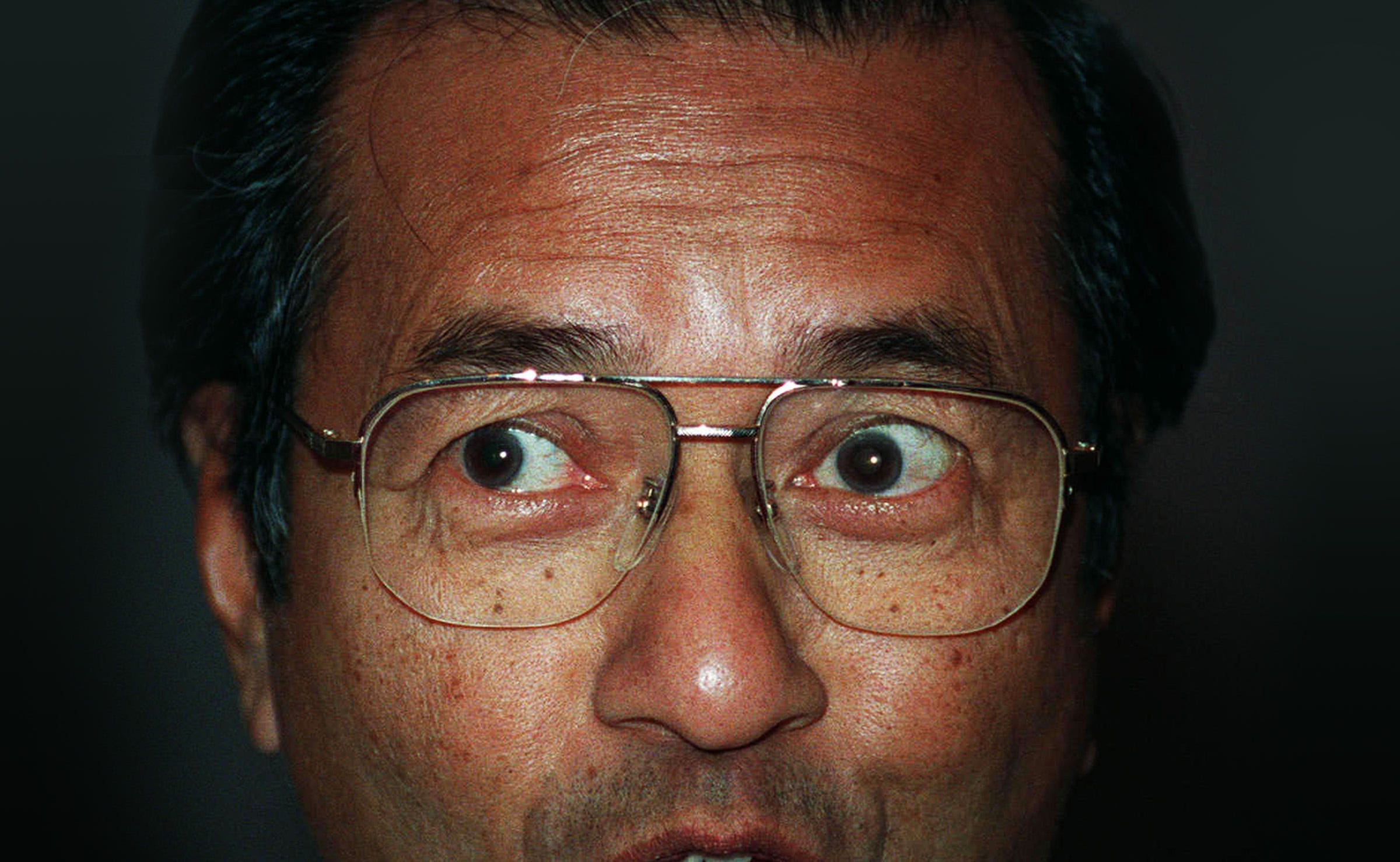

Not only is it not certain if Mahathir is going to step down in 2020, finally handing over the reins to Anwar, who has struggled to push Malaysia towards reforms for the past 20 years. It turns out Anwar himself faces rather duplicitous opposition from within his own ranks in PKR.

At the same time, Bersatu is swelling by recruiting people it was supposed to remove from power, gradually eating up what is left of UMNO.

Right now it is unclear who's going to lead the country in a year or two and, what's worse, nobody can really tell what the direction of the main coalition is going to be either.

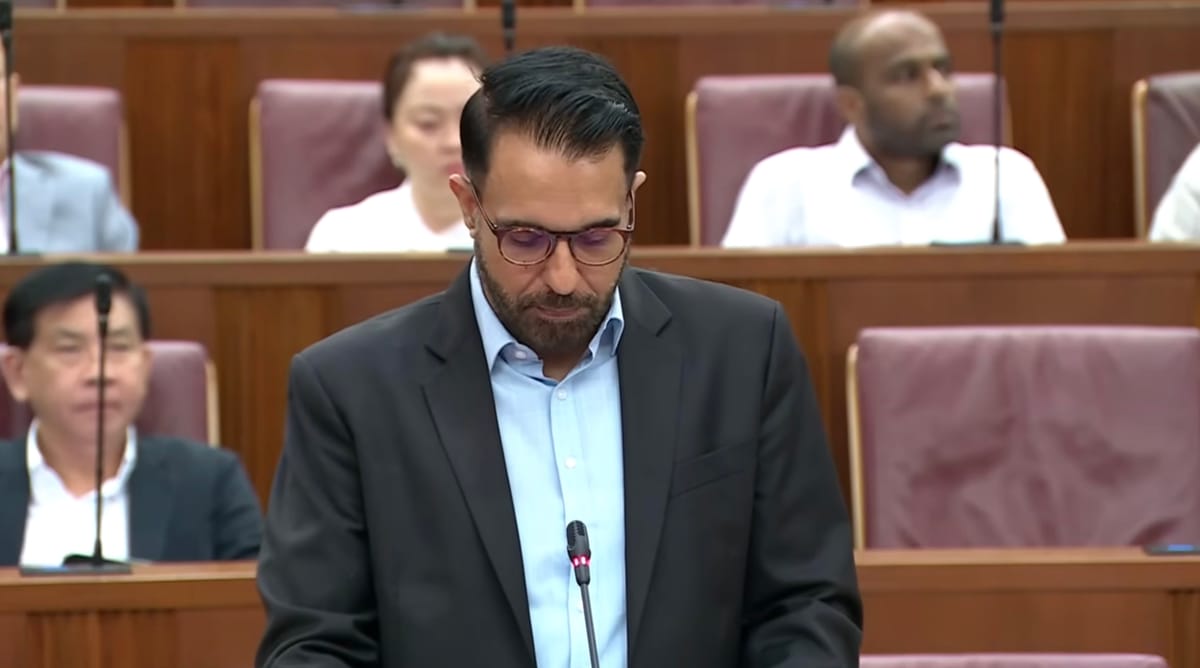

And that better, more organized, more consensual governance is possible is pretty clear from the example of Malaysia's closest neighbour - Singapore - where the ruling PAP has unveiled its new Central Executive Committee and elected its leader, who is set to take over as Prime Minister after elections in 2021. Three years from now.

Any conflicts over power that may have happened have not been put on public display - and once a consensus was established, everybody threw their support behind it.

Isn't that just a much more reasonable way to run a country? So why can't Malaysia do it?

There are many reasons, of course, but one critical factor is the influence of the country's Malay majority. And, unfortunately, Malay politicians are usually chained by their commitments to it (or so they think, at least).

Bumi policies harm Malays eventually

One of the most irrational things that the new government has done is walking back on the most reasonable of the electoral proposals - abolishing the race-based policies to replace them with needs-based aid for the poorest in the society.

And here, we arrive at the core of the problem.

Bumiputera policies have been mainly successful at growing and protecting Malay business elites, who for years have engaged in dubious relations with politicians in charge, leading to widespread cronyism and corruption that eventually brought down the BN government - while costing the society billions of ringgit and years in lost growth.

In the meanwhile, millions of Malays remain relatively poor and are often manipulated by those at the top who like to inflame racial tensions to galvanize support among the rakyat - while primarily serving themselves.

In the process, they have clearly lost sight of what governance is about - leading the country to greater prosperity for all.

The ongoing political conflicts - even within the victorious parties - show that Malay politicians are simply incapable of letting go of their habitual behavior and paranoia about securing Malay support. Governance suffers as a result.

Simply put - Malays are unable to yield to other Malays because they see it as a zero-sum game.

And this is why a non-Malay leader could serve as a unifying actor. Not having a stake in direct representation of the Malay population, he would be free from all questionable influences and power struggles within the community.

If Malay political class can't agree on who should be its true leader, then perhaps the best thing it can do is support an outsider.

A non-Malay Prime Minister would have the advantage of not being tied to various groups of Malay interest - being able, as a result, to deal with them dispassionately. And that would be a welcome change in a country where identity politics are so often abused, frequently stoking sentiments of ethnic superiority, entitlement of the Bumiputeras or manifestations of nationalism in international relations - all of which ultimately harm Malaysia and its own people.

It would not erode the best interests of the Malay population as the government still needs the support of the parliament, where they have a majority.

But it would help put the political conflicts to rest and give the final word to an impartial arbiter leading the country, who would - paradoxically - be more likely to support solutions genuinely benefiting impoverished Malays rather than business elites.

And that could finally bring about the change Malaysians voted for last May.