Returning to the Dover forest one more time - this time with a multi-layered review providing a proper context for understanding how and why certain decisions are made.

In my recent post, published a few days ago, I explained how environmental risks have been gauged through environmental studies conducted across a few years.

But I think the full picture can't be seen without urbanistic aspects that drive development in the area (and why even Clementi forest is still zoned for residential use in the future).

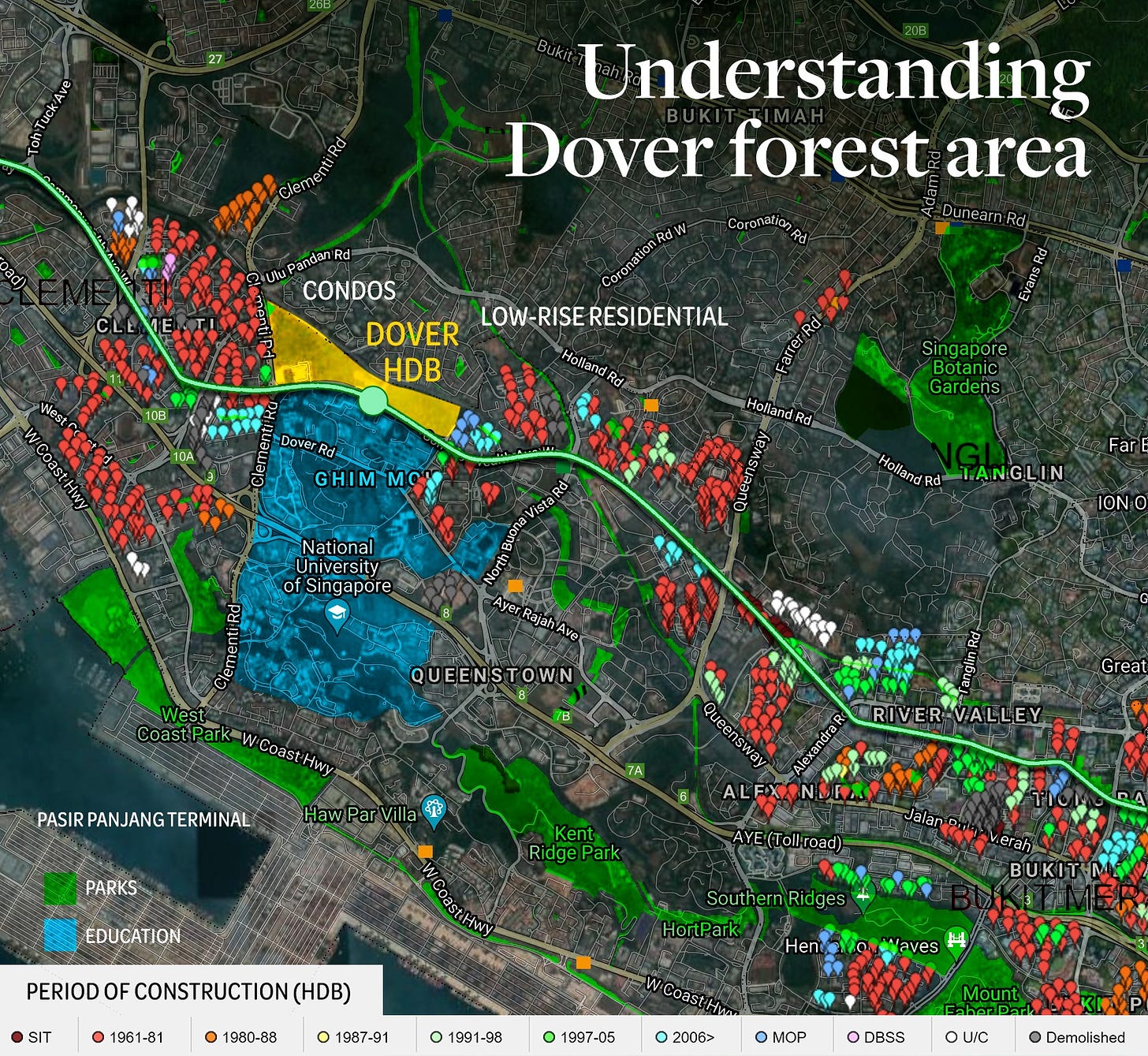

Take a look at the image below:

First, I used data from the excellent site (Teoalida), which catalogues every single HDB by their age (and other features).

It's easy to see that the red markers stand out. They represent HDB blocks built between 1961 and 1981, the oldest under the public housing scheme.

In other words, this very attractive area has not seen much development - for miles in each direction - for about 40-50 years. The most recent project, located at one of the corners of the Dover forest area, was completed in 2017, along Ghim Moh Link, with a few residential towers.

Most of the HDB construction in the past 20+ years has happened in new towns far away from the most attractive central locations.

Now, as many of the buildings are ageing, there is renewed interest in locations known typically for condos or low-rise bungalows. Pinnacle at Duxton has proved to be a great success. There's talk of public housing in place of the Keppel Golf Club, which is due to vacate its premises soon too.

Dover provides another excellent plot of land, long reserved for residential development, with excellent connectivity along EWL and next to attractive areas stretching north to Bukit Timah and south to Southern Ridges.

It's the right time to inject new HDBs there.

Secondly, I went to the Urban Redevelopment Authority's website to pull the zoning master plan for Singapore and overlaid the areas designated as parks (visible in green), not slated for future development, within proximity to the Dover area.

As you can see, even in densely urbanized areas, there are plenty of parks crisscrossing them, providing access to greenery for both humans and animals. You can see the string of the rail corridor there, nearby Singapore Botanic Gardens, parks along Southern Ridges or the West Coast Park next to Pasir Panjang terminal (which, by the way, will be vacated by the port and redeveloped in 20 years time, becoming a part of the Greater Southern Waterfront with more housing, parks, leisure and commercial developments).

Of course, some will say "muh, but parks are not a forest!" - well, neither is Dover, to be frank. It was an undeveloped plot of land that was taken over by randomly growing trees and other plants.

The blue patch on the map is the Polytechnic and NUS area, which is dedicated to education. I placed it there to show how much land is occupied and unavailable for alternative developments just next to the controversial plot.

To the north of Dover land is already hosting high-rise condominiums and low-rise bungalows.

I read some people demanding that the rich move out instead and their properties be taken up for HDB to protect the "forest", but that isn't really possible as expropriation of private owners would be tremendously expensive.

New bungalows in the area fetch prices as high as S$10+ million. Dover forest is 33ha - that's 330,000 square meters. Assuming a single bungalow plot of 1000 sqm. that's 330 bungalows. The sheer cost of compensation for private owners would go into billions of dollars - and that's not counting demolition and necessary infrastructure work for the new housing.

For comparison, between 2015 and 2018, HDB paid approx. S$2,000 per square meter of land in mature estates. On this basis, the entire Dover area may be worth around S$600 million - several times less than pushing private property owners out of their homes.

There's a reason the government keep plots of land in reserve in different parts of the country...

As you can see, there's a lot to consider here besides the purely environmental or aesthetic factors.

It seems to be the right time for HDB to return with more investments to central areas of the city, so they do not morph into exclusive enclaves for the rich, sitting next to ageing public housing that fewer people will want to live in in the future. Balance is necessary - and social reasons are just as important as environmental ones are.

Besides that, there's no lack of greenery nearby (not to mention Singapore's famously dense tree canopy everywhere), and with proximity to the East-West MRT Line and the best schools, it's a prime location, adding to the supply of attractive apartments for regular Singaporeans.

I understand that in a fairly densely packed city, it's nice to have patches of barely touched greenery, but leaving it as is would come with high social and infrastructural costs - and relatively low environmental benefits (it's not a primary forest and is rather small, so its role is limited).

Pursuing many different goals - social, political, economic, infrastructural - requires compromises to maintain balance across many areas at the same time.

It would be good (and a reasonable thing to do) if this complexity is appreciated before callous judgments are made.