It's official, population of Singapore has officially topped 6 million for the first time ever. Unfortunately, whenever this seemingly benign topic reappears in the public eye, it typically causes a stir.

In fact, even the topic of “planning for 10 million people” is so controversial that it has long been used for political gain, pitting the society against the government, in an attempt to win votes, by casting an image of terrible overcrowding as hordes of foreigners descend on the island city-state in the future (since locals clearly do not produce enough children to make it happen).

To plan or not to plan?

The subject receives a periodic boost, like it did two years ago, when former chief city planner and chief executive of Housing and Development Board (HDB), Dr Liu Thai Ker reiterated his view that “a population size of 10 million is not really a ridiculous number for Singapore to make plans to accommodate”.

Over the years we’ve heard or read that Singapore is “planning” for 10 million people or should “plan” to house such a number in the future, or that it is, indeed, a “planning” parameter.

This has often been misleadingly spun as if there was a “plan” to grow Singapore’s population to 10 million. That the government is “planning” to bring in millions of foreigners in response to low local fertility rates.

Meanwhile, what “city planners” (not “population planners”) are talking about is only that 10 million inhabitants is a number that the city has to be prepared for, in case it happens one day in the future.

In their words “planning for” really means “preparing for the possibility of”.

Why is this distinction important? Because the future is unknown but decisions about it have to be made today.

This is to avoid problems if the number of people keeps growing but existing infrastructure is simply unable to support it, what would hurt nation’s prosperity and hurt living standards, reducing its overall attractiveness to foreign capital too.

It also provides redundancy in case some systems fail or the needs of the country grow faster than the population itself, or to cater to the needs of ever growing numbers of visitors.

So, it’s not about assuming that Singapore should have 10 million inhabitants but rather what would be necessary to do to allow the city to handle it:

- How should the MRT look and work?

- How should housing be planned and laid out?

- How should the roads function?

- How should education be provided?

- How should healthcare services be provided?

- How such a population could be fed?

- What is needed in terms of water supply or waste treatment?

And more…

Infrastructural investment typically takes many years of planning and construction, so it has to be undertaken in advance.

Changi Airport handled 65 million passengers every year before the pandemic but it is already planning to expand its maximum capacity to 135 million (up from 85 today) with the addition of Terminal 5 within the next 10 to 15 years, serving many decades into the future.

It is true for everything – MRT, water supply, energy supply, road network, education, healthcare facilities, parks, commerce, office space or sewage.

Let’s take that last one as an example. For decades the now shiny, modern city relied on night soil collectors – which was a very elegant term for running around with buckets of poo, because the sewage network was lacking.

The system was phased out by 1987, after the entire island finally received modern sewers.

But by 1990s plans were already put in place for DTSS – Deep Tunnel Sewerage System – a “superhighway” of 80 kilometers of tunnels built 60m underground to transport waste water to treatment plants on the coasts, in anticipation of growing population that would put further strain on the existing network.

It is expected to work maintenance-free for 100 years, not only helping Singapore get rid of waste water from factories, homes and offices, but also treat it so it can be reused again, as it prepares for self-sufficiency by the the time the second water contract with Malaysia expires in 2061.

At the same time, due to reduced above ground footprint, DTSS has actually released space taken up by now obsolete pumping stations, returning precious land to the very scarce reserves, for redevelopment into housing, offices, commerce or industrial use.

Win-win.

However, if you don’t plan for change you may very well end up with something like the old Kowloon Walled City in Hong Kong:

Can Singapore comfortably support 10 million people?

Contrary to popular beliefs the answer to that is: yes. The Lion City is often seen as a densely populated, overcrowded metropolis, squeezed on a tiny island but that, actually, isn’t true.

Singapore is densely populated as a country - but not a city.

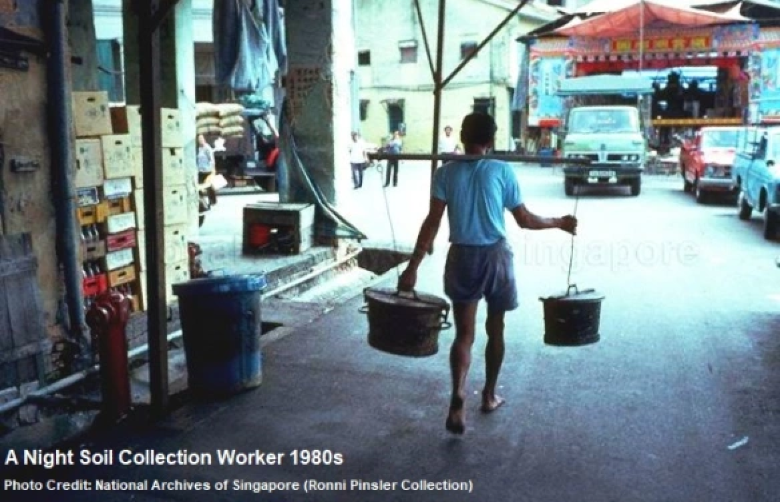

Singapore’s total land area is about 728 sq. km., what gives it population density of about 8000 people per square kilometer at over 5.7 million inhabitants. Even if we take only the currently urbanized area of 566 square kilometers (after all there are nature reserves, military grounds and so on), we’re still only arriving at a bit over. 10,000.

This is a high number for a country, since every other in the world has its average density reduced sharply by the presence of thousands of square kilometers of empty space that SG simply does not have.

While the figure is not exactly small, it is also far from extreme – or even particularly high – for a major urban area, with Singapore ranking comfortably behind many of them.

Of course, comparing different cities is always going to be tricky because their borders often encompass completely different spaces (including rural outskirts, forests etc.).

This is why I have selected a few different examples to illustrate the point (and ignored the truly overcrowded megalopolises of the third world, like Mumbai, Lagos and so on).

Let's start with Manhattan. It is what you could expect of Singapore if its population... tripled in size.

But even that doesn’t give us the full picture, as the island in the heart of the Big Apple receives more than 2 million commuters every single day.

It means that all the packed streets and subways that downtown New York City is known for are really what it would be like if Singapore swelled to over

35 million residents.

What about others? Heck, what is Paris doing on the list!? That is a surprising entry – as few would have it for a densely packed city, particularly in the absence of high rise buildings. Certainly not above Tokyo!

And yet, not only is the capital of France high on the list but its immediate suburb (and a very prosperous one) Levallois-Perret is actually the most densely populated town in the entire Europe, at over 26,000 people per square kilometer. That’s 2.6 times more than urban areas of Singapore.

At this rate the Lion City could become home to… 15 million people – and that is without sacrificing nature reserves and other green areas.

Here's how it looks like:

As you can see, life can be quite pleasant even at more than 2.5 times the population density of SG, without infringing on the natural environment.

Why does Singapore feel crowded, though?

Now, regardless of the figures I am quoting here, I'm sure you may be doubting their accuracy, given your personal experience. After all, isn't Singapore getting packed all the time?

Isn't the MRT crowded? Isn't Orchard Road teeming with people? And why is it so hard to find a place in most food courts?

This is a problem of cities of all sizes, including much smaller ones, in the range of thousands of inhabitants.

It's not that there are too many people – there are too many of them going to the same places at the same time.

I come from a city of a few hundred thousand and trust me – local trains are just as jammed up, if not more, during rush hours as the MRT is. Roads are in gridlock during mornings and afternoons, and people keep complaining about overcrowding.

This is not a function of the number of people inhabiting one place but their distribution in space and time.

In the past 20 years Singapore's population has grown by 50%, from 4 million to 6 million today, but the MRT network more than doubled in size and is being expanded further.

With more interconnectivity between different lines, human traffic them can be distributed more evenly, as everybody has more options to get to where they're going.

Another challenge is the concentration of business in downtown CBD, where thousands head to work every day. The government has been addressing this somewhat, by creating business hubs in other areas too, like Changi Business Park or the latest Punggol Digital District, encouraging companies to move to fringe areas.

The same is true for commercial or entertainment venues, providing more options closer to home.

Relocating businesses around the city instead of concentrating them in one place, reduces the perceived overcrowding during rush hours, enabling the country as a whole to handle more people without compromising the quality of life.

Should Singapore open the borders and let millions in, then?

Again, contrary to what gets many people outraged about the issue, the “10 million plan” was never a deliberate intent to increase the city-state’s population but rather a potentially possible scenario at year 2100 – long after most of us are dead.

And whether it happens has nothing to do with politics but rather with the economy – because immigration is driven by companies seeking qualified workforce, as nation’s prosperity depends on its attractiveness to business.

Laws in Singapore have grown stricter over the years but even without them there’s a natural limit to immigration simply because the city-state has a relatively small domestic market and imposes high living costs on expatriates.

In other words, in a digital, connected world it’s often simpler to work remotely or deploy people where they are most needed rather than bring them to the company headquarters.

At the low end – among construction workers, maids, physical workers – the limitation is simply the local demand for such services. They are only brought in to perform services that Singaporeans themselves need.

The future may very well see Singapore’s population flatline and remain stable over the long term, simply because remote employment is now the mode of operation for a growing number of companies. So, why relocate them to Singapore if they can work from any place in the world?

At the same time, people themselves like the idea of working from home – and that home may be wherever they please.

In addition, the pandemic has accelerated the shift in attitudes and even after it has ended, many locals spend some time working from home, reducing the pressure on the infrastructure and changing our behavioural patterns, keeping people closer to homes.

Nevertheless, the smart thing to do is to get ready for all plausible scenarios. Designing the city for 10 million inhabitants works well not only at the extreme end of this prediction but at 6, 7 or 8 million as well, leaving a healthy margin of error.

Prudence is the foundation of Singapore’s governance and today it is also the basis on which the 10 million figure was established – which may, in the future, be expanded if need be.

As I demonstrated, supporting even 15 million or more, does not need to be impossible or even difficult with appropriate planning, and it wouldn't make Singapore much more crowded than similar urban areas elsewhere in the world.

That said, it should not be treated as a plan, a goal to achieve, but merely a possibility that the agile, forward-thinking, little red dot has to be – as ever – well-prepared to handle.