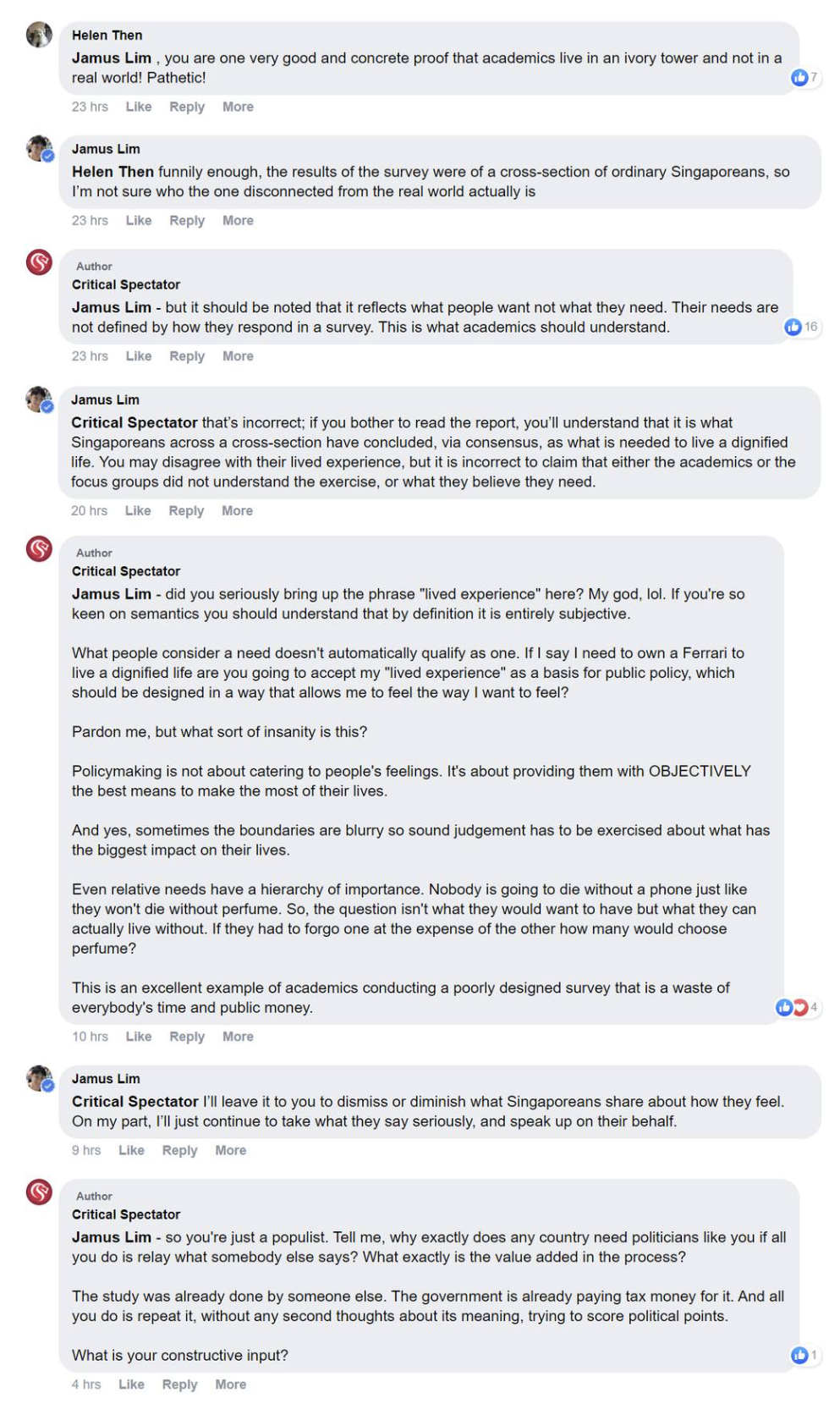

Here's the most interesting part of an exchange I had with Jamus Lim yesterday, under the post about what basic needs in Singapore mean - and whether they should include things like perfume or mobile phone plans.

In case you're not in the loop: a bunch of academics at LKY School of Public Policy, conduct surveys with Singaporeans every two years, asking them about material things they consider necessary in life.

On this basis they then make grand assumptions about whether Singaporeans make enough money or not.

As survey design goes this is an atrocious example of misapplication of statistics, leading to unfounded conclusions that appear to be designed with a particular narrative in mind, rather than a scientific approach aimed at objectively guiding public policy. It is doubly frustrating considering it comes from a school bearing Lee Kuan Yew's name.

This entire study is just a long interview conducted with a focus group comprising local citizens, responding to questions about what they consider a need - which ended up including things like jewellery, perfume or holidays abroad (though I'm still trying to find the actual questions and figures - if you have access to the source, do let me know, it's not published on the study's website).

Its title "Minimum Income Standard" would have you believe it is about fulfilling some fundamental needs but it turns out to be just a wishlist of middle class desires.

And that list – which has no objective basis, since it comes from subjective, personal responses – is now being framed both by the authors as well as Jamus Lim and, I would assume, his colleagues at WP, as a reference for what a minimum living standard in Singapore should be – becoming a de facto entitlement in the process (this is what everybody deserves!).

We can thank Dr Lim for his input on my wall, as it perfectly exemplifies what is wrong with this line of thinking and why it should never be the basis of policymaking - and yet it so often is on the political left around the world.

Jamus Lim unquestioningly accepts the responses of his compatriots, suggesting that I should not dismiss or diminish their feelings about what they consider basic needs.

Let's get this straight – if someone is interviewed and they say they need a nice car, a condo apartment and two weeks in a five star hotel in Dubai, we should all just accept it as a valid input about what constitutes minimum living requirements for them to feel good?

Of course, if you're going to ask a household that makes $50,000 per month what they consider a need, their responses are going to be wildly different from people who make $50,000 per year.

In fact, the definition of a need is going to radically change depending on your current wealth and standards you are used to. Nobody likes to fall, after all.

One of the most famous models of the 1990s, Linda Evangelista, said she doesn't wake up for less than $10,000 per day – a statement outrageous for most regular people but quite understandable at the social rung she occupied.

The government is not a genie from the lamp, fulfilling wishes of all citizens. Its role is to provide conditions in which people can pursue success and earn what they desire to have, that's all.

The only things that can be considered basic needs are largely defined by human biology – like the need to eat, have a roof over your head, bathroom, access to healthcare services etc.

Some additional ones may be added if they objectively and significantly improve a person's chances in e.g. securing employment. Think education and training, telephony; at least basic, usable access to the internet; affordable public transit to get you where you need to go etc.

But you can't unreasonably keep piling onto the list, including aspirational goals, just because survey's respondents would be in a better mood if they were fulfilled.

Unfortunately, what we're seeing is just another example of politicking, little else – trying to score points with the electorate by stoking its appetites through shifting the standards on what should be considered a basic entitlement.

Somebody is going to have to pay for that in the end and it's not going to come out of the pockets of those who are engaging in this misleading behaviour.

What I do not understand, however, is why such politicians are even needed, if all they do is repeat what somebody else already published? As we can see, local academia can already play the adversarial role.

The government has engaged with the authors of the study before. What is the constructive input of parliamentarians who didn't even take part in it, but are just reusing it in public to draw attention to themselves?