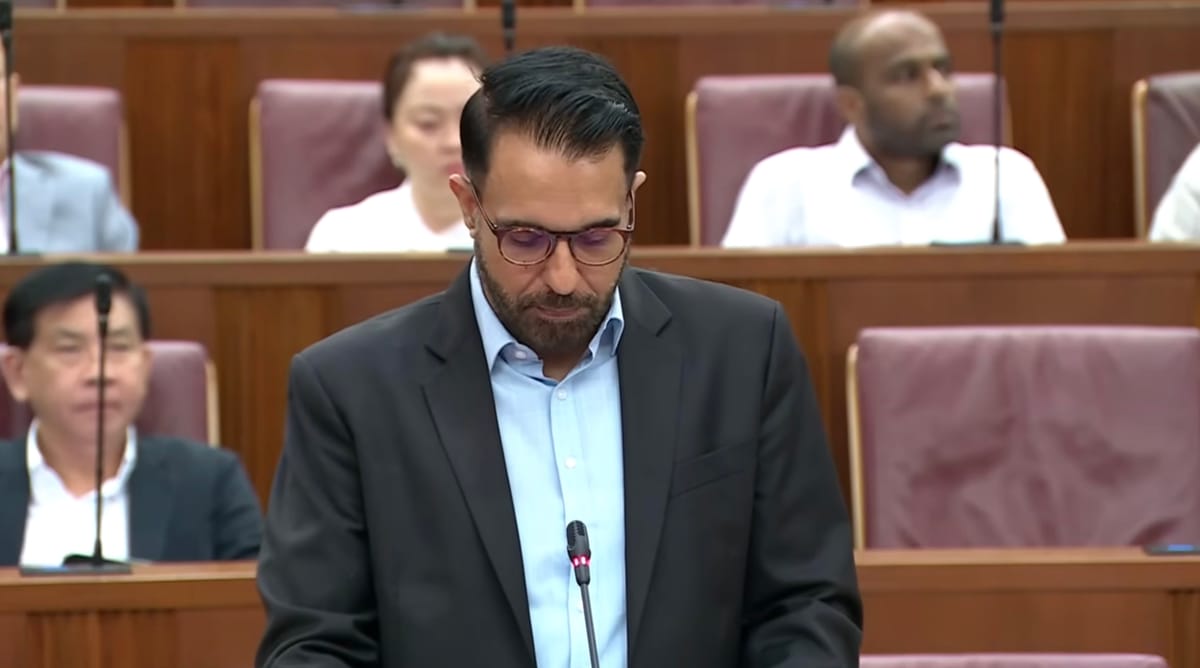

There was one other interesting spectacle during last week's trial of Pritam Singh, and that was his lawyer probing how far he can take his arguments in defence of his client.

On five occasions Mr Andre Jumabhoy, representing Workers' Party leader, found himself corrected by the judge after implying things that tested the boundaries of the truth.

Here they are, as reported by the Straits Times in its live coverage:

1. Shifting the goalposts?

The first run in with the judge happened on October 15, during defence's questioning of Raeesah, with the suggestion that she's adding more things after 3 years.

The judge was apparently forced to interject and remind the defender that she is merely providing answers on the basis of the questions that she was asked in court not during COP.

October 15: ‘You seem to be adding new things three years after the event’, says defence

Mr Andre Jumabhoy points out that Ms Khan’s account of Ms Sylvia Lim asking if her father was waiting for her after the meeting was not mentioned during the Committee of Privileges (COP) hearing.

Ms Khan replies that she believes she had told the police about this, even if she may not have mentioned it to the committee.

Mr Jumabhoy says: “You seem to be adding new things three years after the event.”

The judge interjects, saying that Ms Khan added details based on what was asked in court.

“Was she also asked the same questions at the COP? If that was the case, then you are entitled to ask her,” he says.

2. Schrödinger’s message

I already mentioned this in my previous article, and it's easily the most bizarre, rookie mistake of all – or perhaps a daring attempt to undermine the validity of evidence?

Either way, it's hard to understand how Mr Jumabhoy could question whether Raeesah ever sent the message on August 8, simply on the basis that neither of the recipients responded to it at the time.

October 15: Defence asserts that Raeesah didn’t send Aug 8 ‘take it to the grave’ WhatsApp message to WP cadres

It appears that the Aug 8, 2021, message was never sent, given the lack of a reaction from Ms Loh Pei Ying and Mr Yudhishthra Nathan, says Mr Andre Jumabhoy.

Pritam Singh’s lawyer says this after the prosecution sought a clarification as to whether it was the defence’s position that Ms Raeesah Khan never sent out the message on Aug 8.

The message in question was from Ms Khan to the two Workers’ Party cadres right after her meeting with party leaders, when she had disclosed her lie to them. She told the cadres that the leaders “agreed that the best thing to do is to take the information to the grave”.

The judge interjects, saying Mr Jumabhoy had previously pointed out that the message had been in Mr Nathan’s phone.

“Well, they didn’t react to it,” replies the lawyer.

The judge says there are many possible reasons why the cadres did not react. “We can leave it at that,” he says.

As a reminder, Loh Pei Ying testified that she was busy moving at the time and merely glanced at the message, without giving it a second thought. Meanwhile, Yudhishthra Nathan acknowledged receiving it and thinking it was an instruction to ignore the lie and never speak of it again.

As long shots go, trying to deny that a message that both witnesses received in their phones was actually never sent is a improbably distant one.

Does whether a message is seen or responded to determine its very existence? Is it supposed to be like the famous cat, who was both dead and alive until an observation was made?

3. Goodfellas

In the opening scene of fan-favourite Martin Scorsese film, three accomplices drive out to a forest to bury an annoying member of a mob family.

In a similar spirit, Pritam's defence tried to imply that Raeesah and their two colleagues conspired to "bury the lie" even before meeting the Workers' Party leadership on Aug. 8 – suggesting that it was their idea all along, not inspired by Pritam or anybody else.

October 15: Defence suggests Raeesah and WP cadres decided to bury lie prior to meeting with party leaders

Mr Andre Jumabhoy suggests that the three of them had already decided to continue Ms Khan’s lie on Aug 7, which she denies.

She tells the court that they agreed to wait and see what the Workers’ Party leaders would say. Ms Khan also notes that by saying “they’ve agreed”, she meant that the leaders agreed to take her untruth to the grave.

Mr Jumabhoy then asks if by “they’ve agreed”, Ms Khan is saying that the party leaders agreed with the position the three of them took – that is, to bury the lie.

The judge interjects, saying that it is not a fair question. “She has already said; maybe you can take a look at what she said,” he tells the defence.

In this case, judge Tan reminded the defender to cut back on his repeated questioning given that the answer was already provided and he should refer to it.

4. Raeesah’s impeachment

On the second day of Raeesah's testimony the defence petitioned the judge to impeach her due to the alleged "material contradictions" in her answers.

As I explained in one of my previous posts, calling her credibility into question is the main objective for Pritam, as it would disqualify the most serious evidence in his case.

And while we still have to wait for the outcome of the application, it appears that the judge shot down some of defence's arguments early on, pointing out that there doesn't seem to be much, if any inconsistency in her testimony.

October 16: ‘I don’t see a contradiction, let alone a material contradiction’: Judge Tan

Deputy Principal District Judge Luke Tan reads the agreed statement of facts (SOF), and tells the counsels that he tends to agree with the prosecution that Ms Raeesah Khan’s response to the question on why she did not tell the truth could not be read in isolation as there is a lead-up to it.

He says he does not think there is a dispute that a discussion was made on Oct 3, as the SOF states Pritam Singh had visited Ms Khan at her home.

He adds that it seems Ms Khan was confronted specifically by Law and Home Affairs Minister K. Shanmugam and that prompted her to send the message to Singh.

Judge Tan notes that it could be argued that Ms Khan’s response is consistent with what she said Singh had told her earlier.

“I do not see a contradiction, let alone a material contradiction,” he says.

5. Shifting the goalposts again?

Finally, on October 17, after using a similar manoeuvre against Raeesah, Mr Jumabhoy attempted to use his line of questioning to press Loh Pei Ying towards making a mistake and providing an answer that may at least seem different or contradictory to what she had said before.

October 17: How can you ask if there’s a different answer if question not the same, judge tells defence

The defence asks Ms Loh Pei Ying if Pritam Singh told her during the Aug 10 meeting that the matter of Ms Raeesah Khan’s untruth would not come up again and what she asked him in relation to the issue.

She replies that her memory of the conversation is “fuzzy”.

He continues to press her about the different answer she gave during the Committee of Privileges (COP) hearing regarding her recollection of the meeting.

During her questioning by Second Minister for Law Edwin Tong, Ms Loh said that although they did not talk about the matter explicitly at the meeting, Singh’s acknowledgement of the issue suggested to her that he knew of Ms Khan’s lie.

The judge interjects: “The question that was asked at the COP is not the same question you are asking now. Then how can you ask if there’s a different answer?

Your point seems to be asking why are you giving a different answer, but if you’re asking a different question, I don’t know what else you can expect.”

Again, in this case the judge stepped in and observed that it's irrational for the defender to ask different questions and yet expect the same answers.

It's not the witness' testimony that's changing but what she was asked about.

Of course this line of defence is understandable in the absence of tangible evidence in Pritam's favour, as most of the conversations on the lie and what to do with it took place face to face. This is why it's mostly word against word now.

Given that it's a criminal trial, the standard for evidence is much higher than in a civil one, and guilt has to be proven beyond reasonable doubt.

Pritam's defence can succeed if it can cast enough doubt on the credibility of the witnesses and their motivations throughout the events between August and November of 2021.

Which is why it appears to be trying to apply enough pressure for them to make a mistake, which could be fatal to the prosecution's case.

But only as long as it doesn't go too far.